I used to assume that raw talent and passion were all Indian designers needed to thrive. After all, India has no shortage of creativity – from vibrant crafts to cutting-edge tech. I thought that if you’re a skilled designer in India, success would naturally follow. But the more I dug into the subject, the more I realized that beneath the surface lies a tangle of cultural, educational, and economic forces quietly undermining Indian designers at every turn. Our tech industry soars, yet Indian products are rarely cited for “cutting-edge user experience or aesthetic excellence,” especially compared to the US, Europe or East Asia. This apparent paradox led me on an explorative journey through the layers of India’s design ecosystem, uncovering hidden obstacles that I had never fully appreciated.

The moment it really clicked for me was when I saw a statistic about design education in India: we graduate only 5,000–8,000 design students per year in a nation of 1.4 billion (I will link my sources at the bottom). Suddenly, my own struggles and those of my designer friends started to make sense. I realized that talent alone isn’t enough when an entire system - from our schooling and industry culture to market realities - can hold designers back. To understand why, we need to dig into the historical and cultural sediment that has shaped how design is viewed in India, and then unearth how contemporary conditions continue to challenge those trying to make a mark in design today.

Buckle up! This will be a long one.

Tradition vs. Creativity

I’ll admit: I never questioned the “standard path” when I was younger. Growing up in India, many of us are subtly channeled toward safe, traditional careers - engineering, medicine, finance - while artistic or design-oriented paths are often seen as risky outliers. Creative aptitude alone isn’t always enough to overcome cultural headwinds. In fact, despite a recent rise in students interested in offbeat creative courses, most Indian parents remain skeptical about design as a viable career. There’s a common concern that jobs in art, design, or other creative fields are not “real jobs” - a mindset that, even in 2025, persists in many families. I remember awkward dinner-table conversations explaining what a “product designer” actually does, and sensing the relief when I hastily added that yes, one can earn a living from it.

Part of the problem is our education system’s legacy. For decades, Indian schooling prioritized rote learning and high exam scores over creative thinking. As a student, I was rarely encouraged to question or to create - the exact skills a good designer needs. This “marks over imagination” culture means that by the time someone discovers design, they may have to unlearn habits of conformity. A professor bluntly described it to me: we produce problem solvers who excel at finding the one right answer on a test, but design requires problem finders who ask the right questions. There is, however, some evidence of change (like new art-integrated curricula and design thinking programs in schools), yet the shift in mindset is slow. Many parents still view design and art as extracurricular hobbies rather than legitimate professions. It’s not uncommon to hear of students who, despite showing promise in design school, ultimately drop out under family pressure to pursue something more “stable”.

Another cultural factor runs deeper, something uniquely Indian: our love-hate relationship with jugaad. “Jugaad” is a colloquial term that essentially means a clever makeshift solution - the art of the quick fix. I grew up admiring these ingenious hacks: a farmer rigging a scooter engine onto a cart, or a friend improvising a tool out of spare parts. For a long time, jugaad was even celebrated globally as frugal innovation. But as I investigated, I realized this mindset can be a double-edged sword for designers. While jugaad fosters creativity under constraints, it often cuts corners. There’s a growing recognition that jugaad has become associated with “half-baked, shoddy work”, a far cry from the careful, user-centric process that good design demands. One design critic noted that “jugaad doesn’t follow a design process - it’s essentially a lifehack or shortcut”. I still struggle to define Jugaad to my white friends - mostly because I want to be proud of my roots, but not paint jugaad as some high science. The danger with jugaad is that if businesses and consumers settle for these ad-hoc solutions, they may not strive for long-term innovation or excellence, inadvertently undercutting the role of professional designers. I found myself increasingly convinced that beneath our celebrated ingenuity lay an ingrained tolerance for the “good enough”. That cultural comfort with make-do solutions can work against designers pushing for higher standards - it’s hard to sell the value of thoughtful, research-driven design when a quick fix seems to get the job done today.

If it works, it works. Image Source: Tridib Bordoloi

Lastly, historical context has left its imprint on design culture. After Independence, India’s emphasis was on industrial growth and nation-building through science and engineering. Design was viewed, at best, as a niche or luxury. The fact that for almost 40 years India had essentially one world-class design school (the National Institute of Design, founded 1961) and a few IIT design programs speaks volumes. Design simply wasn’t part of the public consciousness or policy priority for a long time. This meant generations grew up with little exposure to design as a discipline - unlike fields like engineering that benefited from a vast ecosystem of colleges and coaching classes. That historical neglect is a force we’re still fighting: even today, telling someone you want to be an industrial or graphic designer might earn you a puzzled look, unless they happen to know the field. The good news is I’m starting to see glimmers of change in attitudes – younger parents are gradually more open-minded and aware of creative career options than their own parents were. As one report noted, opportunities in fields like design and animation have expanded, so parents today are less anxious if their child chooses a creative career than they were a decade ago. This cultural shift is encouraging, but it’s coming after decades of inertia. Indian designers still often have to justify their career choice and prove its worth to a society that is only beginning to embrace the creative professions.

Education Gaps, Quantity Without Quality

To dig further, I went back to the foundation: design education in India. If I’m honest, I always had a hunch that my design schooling didn’t equip me as well as it could have. (Sorry DSKISD.) After founding and immersing myself in the largest design support network for Indians, YDI, what I found confirms this on a national scale. For a country of our size, the pipeline of well-trained designers is astonishingly small. As mentioned, an industry survey estimated we train on the order of 5–8k designers per year across all disciplines, a drop in the bucket given the huge demand for design in everything from digital apps to consumer products. In fact, a few years ago the British Council projected that India would need around 62,000 designers by 2020 to meet industry needs, yet at the time there were only about 7,000 working designers and 5,000 design students in the whole country. That gap floored me. It’s one thing to feel personally that design talent is scarce; it’s another to see it quantified as tens of thousands of missing designers. No wonder every design job posting in India seems to get a flood of applications and every good designer I know is stretched thin with work - there simply aren’t enough of us to go around if design were adopted at scale.

Yet the answer isn’t as simple as “open more design colleges,” because quantity doesn’t equal quality. And indeed, the 2000s saw a surge of new design institutes – from a handful in 2010 up to 70+ by 2016, and then to 2000+ in 2024 but many of these programs struggled to deliver world-class education. I speak to designers everyday, probably way more than I should, and in every other conversation I am reminded that too many graduates are coming out without the necessary skills for today’s design challenges (let's keep tomorrow's problems aside for a second). They often know how to use tools like Figma or Photoshop, but lack the mindset and methodology of design – things like user research, usability testing, critical thinking. I’ve reviewed portfolios full of sleek app mockups, flashy 3D renders and minimalist logo designs that look great at a glance, often polished to dribbble-worthy perfection, yet I’d struggle to find evidence of the reasoning behind them. It’s as if many students are taught to decorate rather than to problem-solve.

The root of this, I suspect, lies in how design is taught. Too often, Indian design education still mirrors the broader education system’s weaknesses – emphasizing technical skills and following templates over exploratory learning. A designer friend once joked that our class assignments felt like baking recipes: follow these steps, produce a “deliverable,” and you’re done. There was little room to ask why or to iterate on multiple possible solutions. I’ve since learned this is a common critique: our programs often focus on tools and form, not enough on understanding users or context. It’s a “learn the software, copy the popular style, get the job” approach, which leaves a huge blind spot. We end up with grads adept at making things pretty, but not necessarily useful. A part of the problem is non-designers teaching design, mixed with a poor pedagogy and hiring methodology for design teachers. I don't think India lacks talent though, I personally know several exceptional Indian designers producing world-class work, but they are the exceptions, rising despite the system. The average design student here still doesn’t get the kind of holistic training (in human-centered design, in critical inquiry, in collaboration) that one might get in more mature design education ecosystems abroad.

Encouragingly, there’s official recognition of this gap, and efforts to bridge it. I discovered a government press release from 2019 where the India Design Council launched two initiatives: a “Design Education Quality Mark” to accredit and standardize design programs, and a “Chartered Designer” system to certify qualified designers. The fact that these even exist is telling, it’s an admission that the explosion of design courses needed quality control and that design as a profession needed clearer standards. The initiative explicitly aimed to tackle the five challenges India faces in design: scale (not enough designers), quality of design output, quality of education, industry’s low priority for design, and the need for public awareness of design’s value. Reading that felt like a summary of everything I was finding. It’s a bit validating to see the government say yes, we know design hasn’t been prioritized, but we want to change that. New National Institutes of Design (NIDs) have been set up in various states, and a National Design Policy was adopted back in 2007 (one of the few countries to do so) to promote design in industry and education. These are positive steps, no doubt.

Still, translating policy into practice is slow. Many of these reforms are recent, and their impact will take years to trickle down to every college and studio. The reality today is that a young Indian designer often emerges from school carrying two burdens: first, the lingering biases of society (“is this a real career?”), and second, the patchy preparation from their education. I say this as someone who lived that reality - I entered my first internship fluent in software skills but frankly naive about collaborating with users or advocating for design decisions. The learning curve on the job was steep and at times demoralizing. I realized how much more our design schools could do to simulate real-world design challenges - working with communities, interdisciplinary projects, understanding business implications, and so on. Some educators are pushing this direction, emphasizing ethnography, field research, and co-creation with communities rather than just classroom assignments. (infact, I'll give my college DSKISD (RIP) kudos for just that.) This gives me hope that the next wave of Indian designers will be better equipped. But we’re in a transitional phase: the demand for designers is huge and growing, yet the supply (especially of skilled, ready designers) is lagging, which creates stress for those in the field. Until our education system fully catches up, that gap remains one of the quiet forces holding Indian designers back.

Image Source: India Design Council

Design as an Afterthought, and Industry Attitudes

The challenges don’t end once a designer is trained, in many ways, that’s just when they hit the next wall. To see this clearly, I had to understand how Indian industries historically viewed design. It turns out design was, and often still is, seen as a luxury garnish rather than a core ingredient in India’s product and business world. One senior designer told me bluntly: “In most Indian companies, design is treated as decoration, nice to have, but not essential.” This rang true. Think about India’s rise as a tech hub: it wasn’t built on original product design, but on software services and outsourcing. For decades, Indian IT firms were coding back-ends and executing specs given by foreign clients; they weren’t owning product design. In that world, design requirements came from abroad, and our job was just to implement someone else’s vision. The result? A generation of business leaders who never had to integrate design into their strategy, it was something that happened elsewhere.

Even today, I found that many Indian tech and manufacturing companies have not fully woven design into their DNA. It’s improving in pockets, especially with a new breed of startups, but old habits die hard. A common pattern I’ve heard from designers across organizations is this: product decisions are made by business and engineering teams, and only then are designers brought in. This relegates design to a downstream, cosmetic role.

It doesn’t help that design teams in India tend to be drastically understaffed relative to the scope of work. I was amazed (and a bit horrified) to learn that some major Indian tech unicorns function with design teams of 3–5 people. That’s a tiny fraction of what similar-scale companies elsewhere invest in design. It’s a classic catch-22: because design isn’t seen as critical, teams remain small and overworked - and because they’re overworked and brought in late, it’s hard for them to produce the kind of standout design that would prove their value. For many designers in India designing with a full team, and enough breathing room to truly iterate on ideas, is a distant dream. The prevailing business mentality has been to prioritize quick monetization and feature outputs over user experience. One telling example is in the fintech/apps space: Paytm (a homegrown Indian app) vs. Google Pay. Paytm rocketed to success but became infamous for its chaotic, ad-crammed interface, where seemingly every corner was stuffed with new features or revenue-generating schemes. Google Pay entered the same market with a clean, simple UX – fewer features but far easier to navigate. And guess what? Google Pay gained massive adoption and user love, showing that good design and growth can go hand in hand.

We must ask ourselves : Are we designing for immediate profit, or sustainable user satisfaction?

Unfortunately, many Indian companies historically chose the former. It’s a force against designers because if your company cares only about this quarter’s targets, it’s hard to convince them to invest time in a proper design process – research, iteration, polishing details that delight users. Why spend a week refining the onboarding flow when you could push out a new feature that might bump numbers right now? This mindset sidelines designers to the role of “make it pretty after we build it”. It’s demoralizing and it stunts innovation. In fact, I came across a global study (the McKinsey Design Index) that found companies integrating design deeply in their process outperformed industry benchmarks by up to 200% in financial metrics. That’s huge, design isn’t just aesthetics, it’s smart business. And yet, that insight is only slowly trickling into Indian boardrooms.

Why so slowly? Partly, it’s a lack of exposure and precedent. There haven’t been many Indian companies historically that became smashing successes because of great design (we’re starting to see some now in areas like D2C brands and certain apps, but they’re recent). So CEOs haven’t had many local role models to point to. When I talk to design leaders in India, a common thread is the need to educate stakeholders about what design can do - basically advocating for a seat at the table, project by project. That advocacy itself takes energy; it’s an extra burden on designers here that their peers in design-led cultures might not face as acutely. I realized that in India, a designer often has to be a bit of a diplomat and evangelist, not just a craftsperson.

However, I don’t want to paint all companies with one brush. The landscape is evolving. Many startups, especially those founded in the last 5-10 years, have more design-aware founders (often because they’ve seen the difference in Silicon Valley or elsewhere). I have first hand worked with at least 3 Indian startups in the consumer space that brought in design early. These startups are hiring UX researchers, putting designers in leadership roles, and striving for global-quality branding, hardware and interfaces. I’ve been lucky to witness a few such instances where a designer is treated as a true partner in product decisions and the results are visibly better. So the tide is turning, albeit gradually. The key takeaway, though, is that industry attitude has historically been a limiting force: when design is an afterthought, even the most talented designers will struggle to do great work. They’re swimming upstream in organizations that haven’t bought into design. Changing that mentality is perhaps one of the most significant shifts needed for Indian designers to truly flourish.

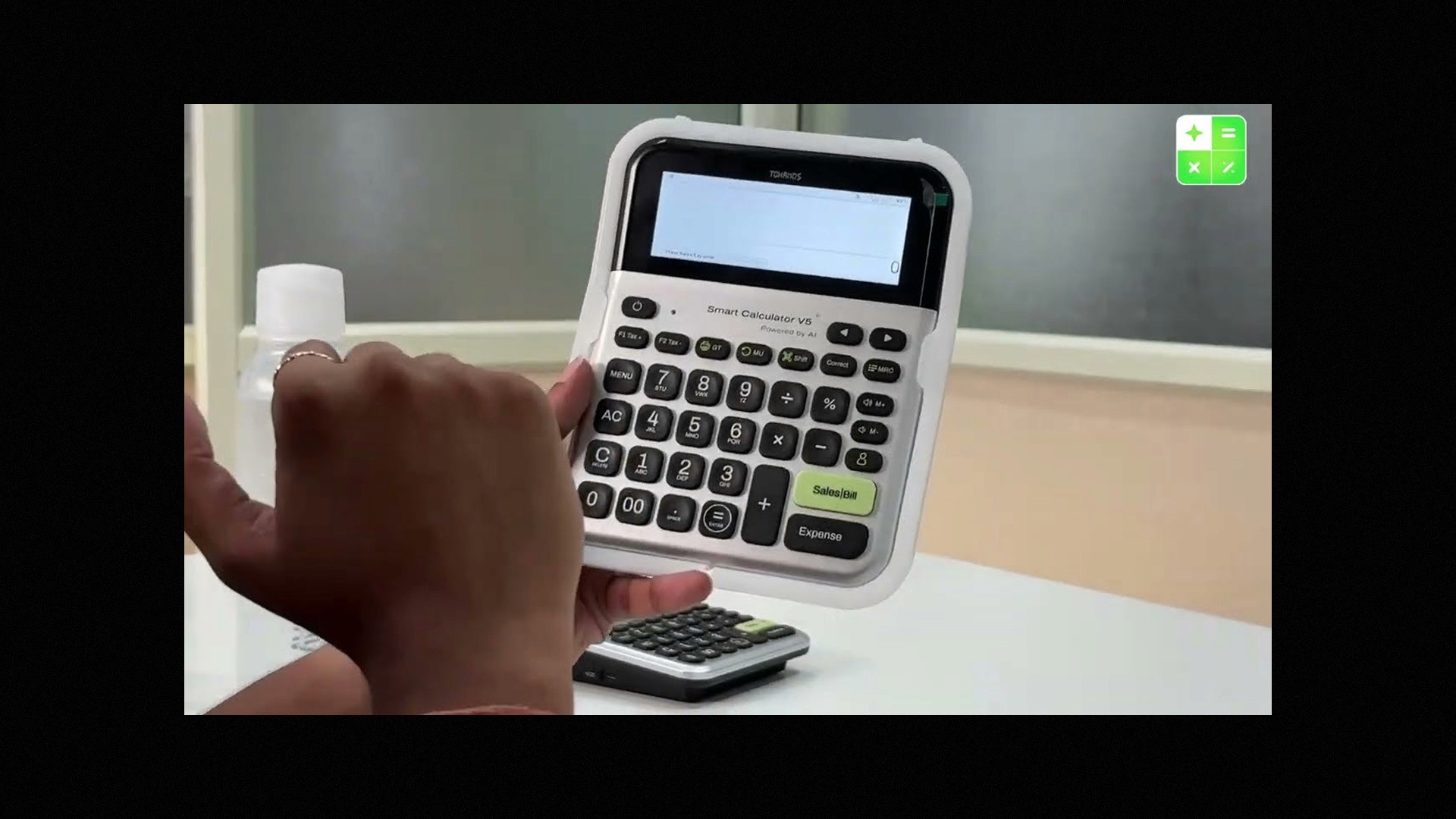

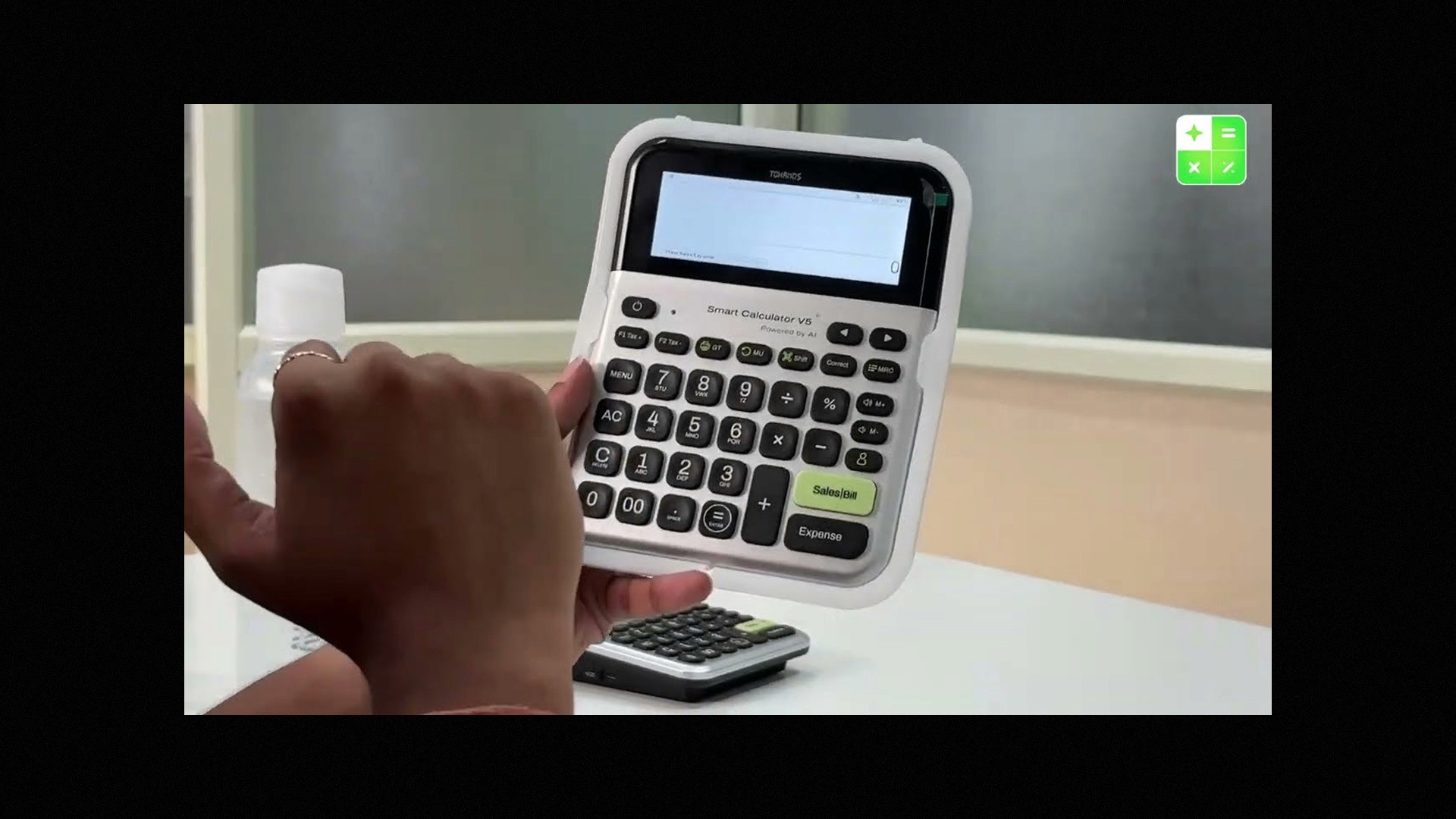

Smart Calculator from an Indian Startup, Tohands, Image Source: Tohands

Economic Pressures and Talent Flight

One thing I kept asking myself through this exploration was: what happens to those Indian designers who do manage to beat the odds - who get the education, have the talent, and fight through the corporate indifference? Increasingly, the answer seemed to be: they leave. This was a painful realization. I knew anecdotally that many of my design school peers aspired to work abroad, where design is more valued, but I didn’t realize how stark the economic disparity was until I saw the numbers. The pay gap for designers between India and the West is staggering. (Spoiler: I'm in the west) According to industry data, the average graphic designer in the US earns around $50k a year, whereas in India the average is only about $3.5k a year. Yes, you read that right – that’s more than a tenfold difference. Even accounting for cost of living, it’s massive. A designer making ₹25,000 a month in India (around $300) might make 10 times that in California. And it’s not just about salary; it’s also about the kind of projects and recognition you get. No wonder so many ambitious Indian designers eye opportunities abroad, whether it’s a UX job in Silicon Valley, a master’s at a prestigious design school, or a fashion apprenticeship in Europe. In fact, the USA (followed by the UK) is the top destination for Indian design students pursuing higher studies, indicating a significant brain drain at the education stage itself. Many of those students end up building careers overseas. I’ve watched it happen: a brilliant classmate goes for an MFA or an internship abroad, then gets scooped up by a company there that appreciates their skill. It’s hard to blame them when the ecosystem back home might offer them a fraction of the pay and perhaps less creative freedom.

This talent exodus is a self-perpetuating problem. I am probably a part of the problem. The fewer top-notch designers remain in India, the harder it is to raise the bar here and mentor the next generation. There’s also a vicious cycle where companies say, “Well, we can’t find senior design talent in India, so we won’t invest in design,” which further pushes talent away. I encountered a striking data point that in some global tech firms, a large fraction of designers (and engineers) are of Indian origin, just not residing in India. It mirrors the general brain drain trend - for example, nearly one-third of IIT graduates leave India, and a huge portion of Indian PhDs and engineers settle abroad in search of better research facilities and work conditions. While I didn’t find a specific statistic for designers, it’s clear that many of our best-trained creatives contribute their genius to companies in the US, Europe, or even other Asian design hubs. This is a loss not just of people, but of mentorship and leadership that could have nurtured the domestic industry. The closest thing to facilitating knowledge sharing at this scale is Young Designers India, where you can literally speak to thousands of Indian designers across 30+ countries, and learn from them first hand.

Beyond salaries, other market forces in India make it hard for designers to thrive. For one, the value of design in the market is still emerging. Clients and consumers here have been very price-sensitive. I’ve seen clients balk at paying for a proper design process – “Just make the logo, we don't need strategy.” kind of attitudes. Smaller companies often opt to copy whatever design is trendy or borrow from global brands, rather than investing in original design work. This not only undercuts individual designers but also means design IP (intellectual property) isn’t strongly respected. A stark example is in fashion and product design: piracy and knock-offs are rampant in India’s design markets. Original fashion designers, for instance, often see their work copied and sold for cheap in the bazaars within weeks. India’s legal framework has provisions (our Designs Act and Copyright Act) to protect designs, but enforcement is patchy and designers often end up in a “legal limbo” trying to prove their rights. One famous Indian couture designer recently lamented that “every design is copied” and had to publicly threaten legal action against plagiarists. In product design, I’ve heard of similar woes - a product designer comes up with a novel idea, but a competitor can make a slight tweak and replicate it without much fear of consequences unless a patent is involved (and patents are expensive and time-consuming to obtain).

This environment can be demotivating. Imagine pouring your creativity into a new furniture line or a graphic identity, only to find cheap clones of it popping up online or in stores, with no robust way to fight it. For independent designers and studios, especially, it’s a serious challenge: the return on innovation is not always guaranteed when copying is so easy. All of this tilts the playing field toward those who cut corners or just mass-produce imitations. It also ties to the broader issue of how design services are valued. When clients see design as a commodity (one logo is as good as another, so get the cheapest), it’s tough for designers who put in that extra thought and originality to compete unless they drastically lower prices.

A significant portion of India’s design activity lives in what’s called the informal economy – think of artisans, traditional craftspeople, freelance designers hustling on their own. I found that over 70% of India’s design and craft economy operates in the informal sector (craft clusters, family businesses, small-scale units). These are incredibly creative folks, but often working with minimal support or recognition. The formal design industry - established firms, corporate design teams, big studios - is just the tip of the iceberg, maybe 30% of the whole. This fragmentation can work against unity in the profession. The artisan weaving in Kutch or the sign-painter in Kolkata historically haven’t been connected to the “modern” designers in metros, each group facing its own economic hardships. The good news is I’m now seeing more collaboration at these intersections (for instance, startups connecting rural artisans with urban designers to create contemporary products). But traditionally, the disconnect between India’s rich craft heritage and its modern design industry meant a lost opportunity to leverage our indigenous strengths. For years, we chased international design standards – trying to be Silicon Valley or Milan – instead of building on local genius.

All these economic factors - low compensation, brain drain, weak IP laws, market undervaluation, and a split economy - create a tough playing field. They push many designers to either compromise or leave.